De Morgan was a pacifist and her art became a form of activism. In Our Lady of Peace (1907), a response to the Boer Wars, a knight pleads for protection and peace, while in The Poor Man who Saved the City (1901), wisdom and diplomacy are advocated as alternatives to military intervention. Later, in The Red Cross (1914-16), angels carry the crucified Christ over a withered landscape pierced by Belgian war graves – a suggestion, perhaps, that the Christian faith is at odds with the brutality of war, but offers us hope of redemption. “You must never praise war,” De Morgan declared in The Result of an Experiment (1909), a book of “automatic writing” co-authored with her husband. “The Devil invented it, and you can have no conception of its horrors.”

Good and evil

The idea of the forces of good and evil acting upon ordinary people was pervasive at this time. “Spiritualism was quite popular,” asserts McMeakin, citing the author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – the creator of Sherlock Holmes – as one of its most famous adherents. Other-worldly beliefs, she says, were “probably the result of the turmoil, the massive changes happening in society leading up to the turn of the century, plus a period of many wars, which would have had an impact on their view of the world”. Doubtless, De Morgan was also influenced by her mother-in-law, Sophia, a well-known spiritualist and medium. With so many lives lost, it was no doubt tempting to believe that you could reconnect with the departed.

Trustees of the De Morgan Foundation

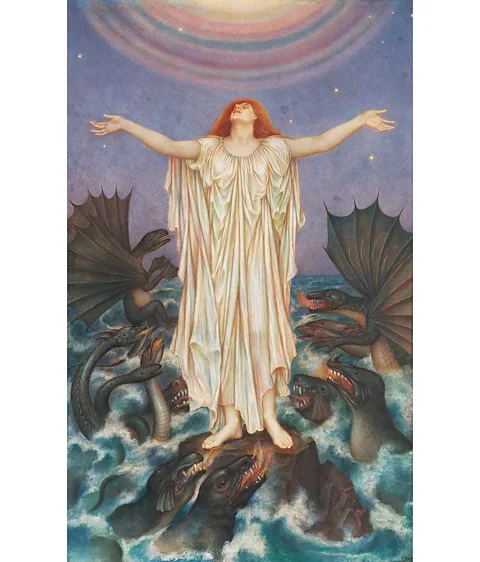

Trustees of the De Morgan FoundationFor De Morgan, materialism was in opposition to spirituality, and many of her works conflate the pursuit of wealth with death. Crowns, as worn by the winged serpents in Death of the Dragon, are a repeated motif denoting greed and miserliness. In Earthbound (1897), an avaricious king in a gold cloak patterned with coins is about to be overwhelmed by the angel of death, while in The Barred Gate (c.1910-1914), a similar figure is denied entry to Heaven.

Often with her apocalyptic scenes, there is a glimmer of hope, or a part of the painting that is calm – Jean McMeakin

With the future so uncertain, De Morgan places the importance of spiritual fulfilment and happiness at the centre of much of her work. In Blindness and Cupidity Chasing Joy from the City (1897), for example, “Cupidity” is personified as a crowned figure clutching treasures who is driving away “Joy” in the form of an angel. Here, as in Death of the Dragon, the central characters are chained, suggesting trapped souls.

In The Prisoner (1907-1908), the barred window and a woman’s chained wrists make captivity a metaphor for gender inequality, hinting at the De Morgans’ support for universal suffrage (Evelyn was a signatory of at least two important petitions, while her husband was vice-president of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage). The theme recurs in Luna (1885), where the rope-bound body of a moon goddess, a mythological figure of feminine power, functions as a metaphor for a woman’s struggle to influence her own destiny.